We don’t just connect cables — we connect logic. IPv4 keeps the digital world on the map.

To understand IPv4 is to read the map of the Internet — the way every packet finds its way home.

First Listen: let your ears lead the way before your mind takes notes.

📻 FZ2CCNA Radio:

Then read: let your eyes explore before your mind starts to explain.

Why IP Addresses Exist

Think about how the postal system works. Every house, apartment, or business has its own unique address—without it, mail would wander endlessly, never reaching the right door.

Now imagine the internet as a massive, ever-growing city. Inside it live billions of digital “homes”: laptops, phones, routers, printers, smart TVs, even your fridge. Each one constantly sends and receives information—just like people sending letters or packages.

To keep this digital mail from getting lost, every device needs a precise identifier that tells the network where it is and how to reach it. That’s what an IP address does: it’s the device’s unique “street address” on the internet.

Just as a postal address helps mail carriers deliver letters from one city to another, an IP address helps routers deliver data packets from one device to another—across neighborhoods, countries, or continents.

Without IP addresses, data would have nowhere to go. Messages, videos, and websites wouldn’t know where to land. In short, IP addresses make communication possible—they give every device a place to call home in the digital world.

What “IPv4” Means

The v4 in IPv4 stands for Version 4 of the Internet Protocol — the set of digital rules that allows computers to talk to each other across networks. It’s the fourth generation of this protocol and the one that built the modern Internet as we know it.

Even though its successor, IPv6, was introduced to handle the growing shortage of IP addresses, IPv4 is still the most widely used system worldwide. Most routers, servers, and network devices continue to rely on it every day.

The 32-Bit Foundation

Every IPv4 address is made up of 32 bits — that’s 32 individual binary digits (ones or zeros).

If we were to write one of these addresses in binary form, it would look something like this (simplified example):

11111111.11111111.11111111.00000000

Each group of 8 bits is called an octet, and together they make up the full 32-bit address:

8 bits × 4 octets = 32 bits total

Each bit is like a tiny switch that can be on (1) or off (0). By combining different patterns of these switches, IPv4 can create over 4 billion unique addresses (2³² = 4,294,967,296) — enough for the early Internet, but not for today’s massive number of devices.

Reading and typing long strings of ones and zeros isn’t practical for humans, so IPv4 addresses are usually written in a friendlier format called dotted-decimal notation.

In this system, each octet is converted from binary to its decimal equivalent and separated by dots:

11000000.10101000.00000001.00000100 = 192.168.1.4

This makes it much easier to read, remember, and type — especially for network engineers and system administrators who work with IP addresses daily.

Why It Matters

IPv4 is more than just numbers separated by dots — it’s the logical addressing system that helps the Internet find its way home. Every email sent, every web page loaded, and every device connected depends on this addressing structure to reach the right destination.

Understanding IPv4 isn’t just about memorizing formats — it’s about understanding the language of the Internet itself.

Dotted-Decimal Notation

Dotted-Decimal Notation is a human-friendly way to express a 32-bit binary IPv4 address. Each group of 8 bits (one octet) is converted into its decimal equivalent (a number between 0 and 255) and separated by a dot (.).

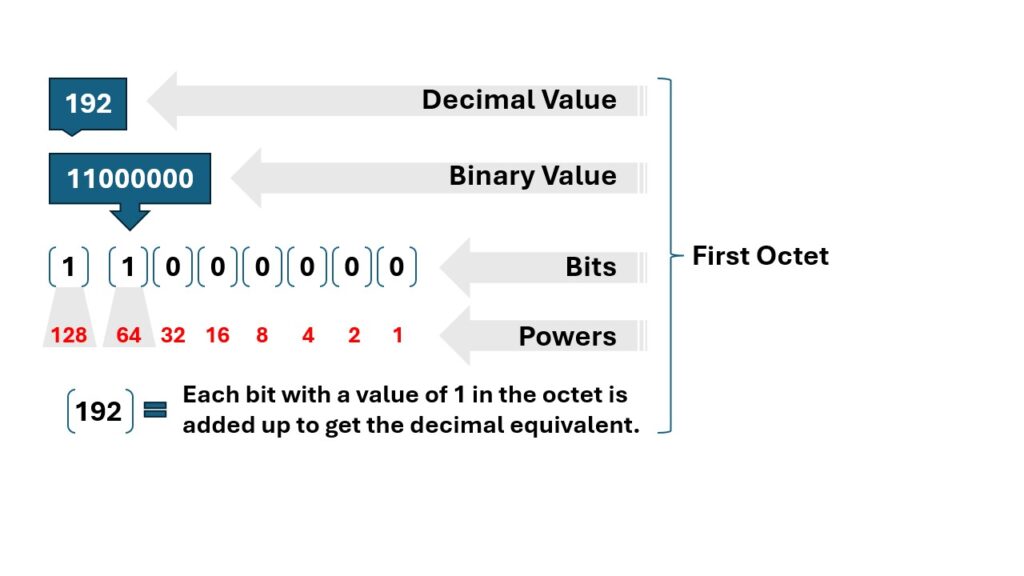

The illustration explains how the binary value 11000000 becomes the decimal value 192, focusing on the first octet of an IPv4 address.

Decimal and Binary Relationship

- The top blue box (192) represents the decimal value of the octet.

- The next row (11000000) shows the binary equivalent — 8 bits that make up one octet.

Each bit (binary digit) can be either 1 (on) or 0 (off). A bit set to 1 means that its corresponding power of 2 contributes to the total decimal value.

Bit Breakdown

- The binary value

11000000is split into eight positions (bits):1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 - Each bit corresponds to a power of two, listed below in red:

128 64 32 16 8 4 2 1

The Math Behind It

To calculate the decimal equivalent:

- Only bits that are 1 are counted.

- In

11000000, only the first two bits are 1 in positions for 128 and 64. - Add those together:

128 + 64 = 192

That’s how the binary sequence 11000000 becomes the decimal number 192.

The Explanation Sentence

“Each bit with a value of 1 in the octet is added up to get the decimal equivalent.”

This means:

- Look at every bit in the octet.

- Wherever you see a 1, take its decimal weight (power of two).

- Add those weights together.

- The result is the decimal representation of that binary octet.

Conceptual Takeaway

Each octet = 8 bits = 1 byte.

Each bit position doubles in value from right to left (powers of two).

The decimal number tells us which bits are “on.”

This is how IP addresses are stored and understood by computers — binary for machines, decimal for humans.

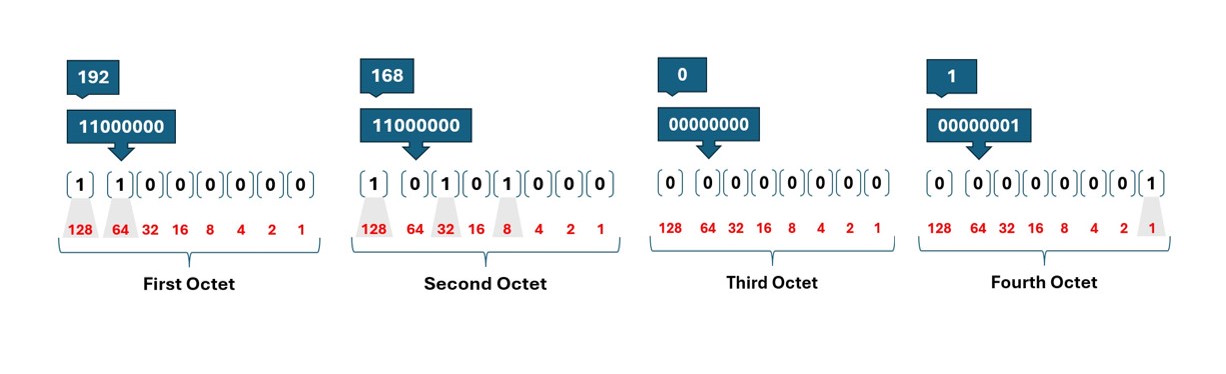

The image below applies the same logic shown earlier, illustrating how all four octets together form the IPv4 address 192.168.0.1.

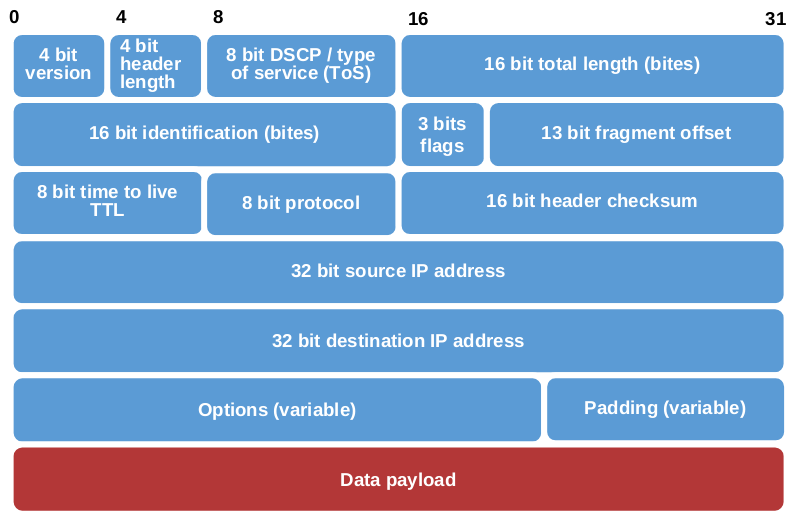

IPv4 Header

Think of the IPv4 header as the envelope of a digital letter. When you send a physical letter, you write:

- The sender’s address (who’s sending it)

- The recipient’s address (who should receive it)

- The postal service instructions (priority, route, etc.)

- The contents (the message itself)

That’s exactly what IPv4 does for data in a network. Every packet on the Internet has:

- An envelope (the IPv4 header)

- A payload (the actual data, such as a TCP segment or a UDP datagram)

Routers don’t care what’s inside the payload — they only read the header to decide where to forward the packet next.

Structure of the IPv4 Header

The IPv4 header contains all the information a router needs to forward packets correctly. A standard IPv4 header is 20 bytes long, but it can be longer if options are included.

Here’s the structure

| Field | Size (bits) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Version | 4 | Defines the IP version (always 4 for IPv4) |

| IHL (Internet Header Length) | 4 | Header length in 32-bit words |

| DSCP / Type of Service | 8 | Quality of Service (QoS) and priority |

| Total Length | 16 | Entire packet size (header + data) |

| Identification | 16 | Used for fragmentation and reassembly |

| Flags | 3 | Controls fragmentation |

| Fragment Offset | 13 | Position of this fragment in the original datagram |

| Time to Live (TTL) | 8 | Limits the lifetime of a packet |

| Protocol | 8 | Specifies upper-layer protocol (TCP, UDP, ICMP, etc.) |

| Header Checksum | 16 | Detects header corruption |

| Source IP Address | 32 | IP address of the sender |

| Destination IP Address | 32 | IP address of the receiver |

| Options | Variable | Optional parameters |

| Padding | Variable | Ensures the header is a multiple of 32 bits |

Deep Dive into Each Field

Version (4 bits)

This tells the router which IP version the packet uses.

- Value

4= IPv4 - Value

6= IPv6

If a router receives a version it doesn’t understand, it drops the packet. It’s like seeing “U.S. Mail” vs. “International Courier” on an envelope — you instantly know how to process it.

IHL – Internet Header Length (4 bits)

Specifies how long the header is, in 32-bit words.

Each word = 4 bytes.

The minimum value is 5 (for a 20-byte header).

If options are present, the IHL increases.

Example: If IHL = 6 (6 × 4 = 24 bytes.)

Think of IHL as the number of lines before the “body” of the letter starts. If extra instructions are added (like “handle with care”), the header becomes longer.

DSCP / Type of Service (8 bits)

Originally called “Type of Service (ToS)”, this field is now divided into:

- DSCP (Differentiated Services Code Point) — 6 bits for QoS classification

- ECN (Explicit Congestion Notification) — 2 bits for congestion control

Routers use DSCP values to prioritize packets (e.g., voice traffic > file downloads).

Example DSCP values:

AF41for high-priority video conferencingCS0for best-effort traffic

It’s like a shipping label: “Fragile,” “Express,” or “Standard.” Routers use it to decide how urgently to forward packets.

Total Length (16 bits)

This field defines the entire packet size (header + payload), in bytes.

The maximum is 65,535 bytes (2¹⁶ – 1).

Routers use this to determine how much data to read from the incoming frame.

Example:

- Header: 20 bytes

- Data: 1,480 bytes

- Total Length = 1,500 bytes (fits in an Ethernet frame)

It’s like the weight of a package — you need to know if it’s too heavy to fit in your delivery truck (MTU).

Identification (16 bits)

Each IP datagram gets a unique ID number when sent. If fragmentation occurs, all fragments share the same ID so the receiver knows how to reassemble them. Imagine mailing a book in several envelopes; you’d label each envelope “Book #123, Part 1/3,” “Book #123, Part 2/3,” etc.

The ID number keeps the pieces together.

Flags (3 bits)

These bits control fragmentation behavior:

- Bit 0: Reserved (always 0)

- Bit 1: DF (Don’t Fragment) — if set, packet must not be fragmented

- Bit 2: MF (More Fragments) — set on all fragments except the last one

If a router needs to fragment a DF-marked packet, it drops it and sends an ICMP “Fragmentation Needed” message. Like writing “DO NOT FOLD” on a paper. If the envelope won’t fit through a slot, it must be returned instead of bent.

Fragment Offset (13 bits)

Indicates where each fragment belongs within the original datagram.

Measured in 8-byte units.

Example:

If a fragment offset = 100 → fragment starts at byte 800 of the original packet. Page numbers in a long document — they tell you how to put the story back in order.

TTL – Time To Live (8 bits)

This is a safety mechanism that prevents packets from looping forever. Each router that forwards the packet decrements TTL by 1. If TTL reaches 0 → the router discards the packet and sends an ICMP “Time Exceeded” message back.

Typical initial values:

- Windows: 128

- Linux: 64

- Cisco routers: 255

Like a self-destruct timer on a message — if it doesn’t reach the destination in time, it destroys itself.

Protocol (8 bits)

Specifies the upper-layer protocol inside the IP packet.

Examples:

| Protocol | Number |

|---|---|

| ICMP | 1 |

| TCP | 6 |

| UDP | 17 |

| OSPF | 89 |

| GRE | 47 |

Routers use this field to hand the packet to the correct layer 4 process. It’s like the “contents” label on a box — “This contains glassware,” “This contains documents,” etc.

Header Checksum (16 bits)

A checksum computed only over the IPv4 header (not the payload). Routers recalculate this each time TTL changes. If corruption is detected the packet is discarded. Like verifying the integrity of the envelope’s address before opening it.

Source IP Address (32 bits)

The IP address of the sender. Routers use it to reply or send ICMP errors.

Example: 192.168.10.1

Destination IP Address (32 bits)

The IP address of the receiver. Routers use it for forwarding decisions.

Example: 10.1.1.5

Like the “To” and “From” fields on a postal envelope.

Options (Variable)

Optional features for:

- Security tags

- Source routing (obsolete)

- Timestamping

Not commonly used today because they slow down routing. Special delivery instructions like “Only deliver after 5 PM” — rarely used because they complicate routing.

Padding (Variable)

Used to make sure the header size is a multiple of 32 bits (4 bytes). Routers read data in 32-bit chunks, so padding keeps things aligned. Extra blank space to make sure all paragraphs end on an even line.

IPv4 Header Graphic Representation

IPv4 Header in Action

Let’s visualize this in the Cisco IOS CLI.

Viewing IP packet details on a router

R1# debug ip packet detailYou’ll see output similar to:

IP: s=192.168.1.10 (local), d=8.8.8.8, len 84, ttl 64, prot=1 (ICMP)- Source = 192.168.1.10

- Destination = 8.8.8.8

- Total length = 84 bytes

- TTL = 64

- Protocol = 1 (ICMP)

Tracing TTL expiration

R1# traceroute 8.8.8.8Each hop reduces TTL by 1. When TTL = 0, the router sends an ICMP “Time Exceeded” — that’s how traceroute maps the path.

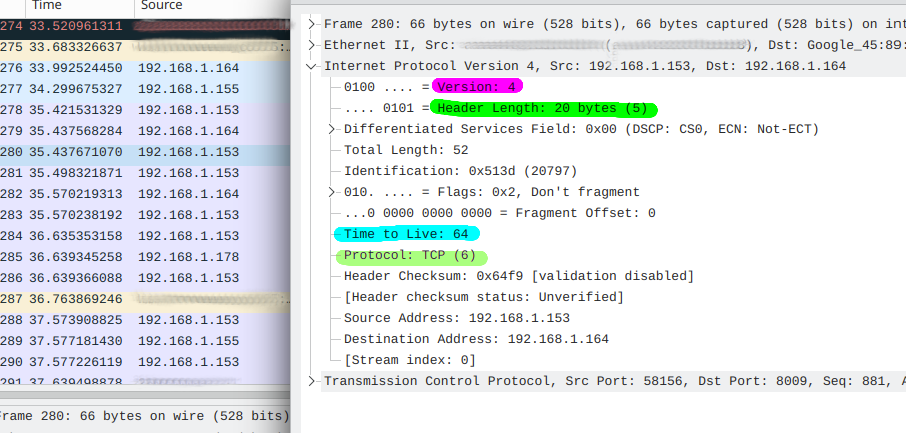

Capturing the IPv4 header via Wireshark

When analyzing packets:

- Version = 4

- Header Length = 20 bytes

- TTL decreases by 1 each hop

- Protocol = 6 (TCP) or 17 (UDP)

This is invaluable when troubleshooting path issues or packet drops.

Real-World Applications

QoS (Quality of Service)

- Routers use the DSCP field to prioritize voice or video over bulk data.

Security

- Firewalls match protocol and source/destination IP fields to allow or block traffic.

Network Diagnostics

- Tools like ping and traceroute rely on the TTL and ICMP protocol fields.

Fragmentation Troubleshooting

- If MTU mismatches occur, packets get fragmented — use the Identification, Flags, and Fragment Offset fields to understand it.

Key IPv4 Troubleshooting CLI Commands (Cisco)

| Purpose | Command | Description |

|---|---|---|

| View IP interfaces | show ip interface brief | Lists all IPs and status |

| Check routing table | show ip route | Displays next hops and destinations |

| Debug IP packets | debug ip packet | Monitors packet movement |

| Disable debug | undebug all | Stops all debugging |

| Verify connectivity | ping [IP] | Tests reachability using ICMP |

| Trace packet path | traceroute [IP] | Uses TTL to reveal hops |

| View fragmentation | show ip traffic | Displays fragment statistics |

| Capture header info | show ip protocols | Shows routing and protocol details |

The Soul of IPv4

The IPv4 header is the control panel of the Internet. Every bit tells a story:

Version & IHL define structure.

DSCP defines priority.

Total Length defines size.

Identification, Flags, Offset enable fragmentation.

TTL & Checksum ensure safe delivery.

Protocol, Source, Destination determine who talks to whom.

Like an envelope, it doesn’t carry the message — it carries the instructions for how that message travels the world.

A Digital Neighborhood Story

Picture the early Internet — a small, buzzing town in the 1980s, when computers still had floppy disks and network engineers wore pocket protectors instead of smartwatches.

This new “Internet Town” was growing fast: governments, universities, and tech companies were all lining up for addresses — digital homes where their data could live.

But there was a problem…

Not every resident needed the same number of houses.

Some were giant digital empires with thousands of computers.

Others were tiny startups, maybe just one dusty server in a garage.

So the architects of the Internet decided to do what any good city planner would:

They divided the land into districts — each one with a different size of neighborhood.

- Class A was like a megacity, vast enough to hold millions of homes — reserved for giants like government agencies and telecoms.

- Class B was a mid-sized city, perfect for universities or corporations with a few thousand devices.

- Class C was your cozy cul-de-sac, just big enough for a local business or small LAN.

Each class came with boundaries (network bits) and house numbers (host bits).

Together, they formed what we now call classful addressing — the original zoning law of the Internet.

It worked beautifully… until the town exploded.

By the 1990s, there were more networks than anyone expected. The megacities had empty skyscrapers, while small neighborhoods were overcrowded. The system couldn’t scale.

That’s when CIDR — Classless Inter-Domain Routing — arrived, like a visionary urban planner, tearing down the rigid fences and allowing engineers to resize networks freely. No more fixed-size districts — just flexible blocks that fit real-world needs.

IPv4 Address Basics

An IPv4 address is 32 bits long, usually written in dotted decimal form:

192.168.1.10Each section (octet) represents 8 bits, so:

192.168.1.10 = 11000000.10101000.00000001.00001010 (binary)Each address has two parts:

- Network portion — identifies the network.

- Host portion — identifies a device within that network.

The subnet mask tells where one ends and the other begins.

The Five Historical IPv4 Classes

IPv4 originally had five classes (A through E). Let’s break them down:

| Class | Leading Bits | 1st Octet Range | Default Mask | # of Networks | Hosts per Network | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 1–126 | 255.0.0.0 | 128 (0 & 127 reserved) | ~16.7 million | Very large networks (ISPs, gov’t) |

| B | 10 | 128–191 | 255.255.0.0 | 16,384 | ~65,000 | Medium networks (universities, companies) |

| C | 110 | 192–223 | 255.255.255.0 | 2,097,152 | 254 | Small networks (LANs, offices) |

| D | 1110 | 224–239 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Multicasting |

| E | 1111 | 240–255 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Experimental, reserved |

Deep Dive into Each Class

Class 🄰

- First bit = 0

Range:1.0.0.0to126.255.255.255 - Default mask:

255.0.0.0or/8 - Network bits: 8

- Host bits: 24

- Number of networks: 2⁷ = 128 (but 0 and 127 are reserved)

- Number of hosts per network: 2²⁴ – 2 = 16,777,214

A Class A network is like a nation — you can have millions of citizens (hosts) under one government (network ID).

Examples:

10.0.0.0/8 private (RFC 1918)

11.0.0.0/8 DoD (U.S. Department of Defense)CLI verification:

R1# show ip interface brief

Interface IP-Address OK? Method Status

Gig0/0 10.1.1.1 YES manual upHere, 10.1.1.1 belongs to a Class A network.

Class 🄱

- First two bits = 10

Range:128.0.0.0to191.255.255.255 - Default mask:

255.255.0.0or/16 - Network bits: 16

- Host bits: 16

- Networks: 2¹⁴ = 16,384

- Hosts per network: 2¹⁶ – 2 = 65,534

Class B network is like a city — it has thousands of homes (hosts), organized under one municipal boundary (network).

Example:

172.16.0.0 to 172.31.255.255 → private Class B rangeCLI example:

R1(config)# interface gig0/1

R1(config-if)# ip address 172.16.5.1 255.255.0.0This interface is configured within a Class B network.

Class 🄲

- First three bits = 110

→ Range:192.0.0.0to223.255.255.255 - Default mask:

255.255.255.0or/24 - Network bits: 24

- Host bits: 8

- Networks: 2²¹ = 2,097,152

- Hosts per network: 2⁸ – 2 = 254

Class C network is like a neighborhood — you have a small number of houses (hosts) under one street address (network ID).

Examples:

192.168.0.0 – 192.168.255.255 → private rangeCLI Example:

R1(config)# interface gig0/2

R1(config-if)# ip address 192.168.1.1 255.255.255.0This interface is configured within a Class C network.

Class 🄳 (Multicast)

- First four bits = 1110

→ Range:224.0.0.0to239.255.255.255 - Used for multicast — one-to-many communication.

- No subnet mask, since it doesn’t represent hosts.

Think of Class D as broadcast TV — one source (station) sends data to many receivers (TVs).

Examples:

224.0.0.1 All hosts multicast

224.0.0.2 All routers multicastCLI:

R1(config)# ip igmp join-group 224.0.0.1This command makes the interface listen to multicast group 224.0.0.1.

Class 🄴 (Experimental)

- First four bits = 1111

Range:240.0.0.0to255.255.255.255 - Reserved for experimental or research purposes.

- Not used in production networks.

Like a lab prototype — not for public use, but for testing new ideas.

Private vs. Public IPs (RFC 1918)

Within Classes A, B, and C, specific ranges are reserved for private networks — meaning they are not routable on the Internet.

| Class | Private Range | Default Mask |

|---|---|---|

| A | 10.0.0.0 – 10.255.255.255 | 255.0.0.0 |

| B | 172.16.0.0 – 172.31.255.255 | 255.255.0.0 |

| C | 192.168.0.0 – 192.168.255.255 | 255.255.255.0 |

Think of private IPs as phone extensions inside a company — they work internally, but to call the outside world (Internet), you need a public number (NAT).

CLI check:

R1# show ip route

C 192.168.1.0/24 is directly connected, Gig0/0

Here, 192.168.1.0/24 is a private Class C network.

Calculating Address Classes from an IP

To identify a class:

- Look at the first octet (leftmost).

- Use this range:

| Range | Class |

|---|---|

| 1–126 | A |

| 128–191 | B |

| 192–223 | C |

| 224–239 | D |

| 240–255 | E |

Example:192.168.10.5 → starts with 192 → Class C172.20.5.10 → starts with 172 → Class B10.1.1.10 → starts with 10 → Class A

CLI trick:

R1# show ip interface gig0/0

Internet address is 192.168.1.1/24From /24, you know it’s in Class C default range.

Why Classful Addressing Died

By the 1990s, the Internet was growing explosively — and classful addressing wasted space.

For example:

- A small company with 300 devices couldn’t fit in a Class C (254 hosts).

- But a Class B (65,534 hosts) was too large.

So, engineers developed CIDR (Classless Inter-Domain Routing) — allowing flexible subnet masks like /27, /19, etc., instead of being tied to classes. CIDR brought subnetting and supernetting, which are key CCNA skills (and the next topic in your study plan).

Key Cisco CLI Commands for IPv4 Class and Address Troubleshooting

| Purpose | Command | What It Shows |

|---|---|---|

| Show all interfaces with IPs | show ip interface brief | Lists addresses, up/down state |

| Show detailed interface info | show ip interface [int] | Subnet mask, broadcast, class info |

| Show routing table | show ip route | Which networks are connected or learned |

| Show ARP table | show ip arp | IP ↔ MAC mapping for local network |

| Show protocols | show ip protocols | Routing protocol details |

| Ping test | ping [IP address] | Verifies connectivity |

| Trace route | traceroute [IP address] | Displays hop path (TTL behavior) |

| Debug IP | debug ip packet | Real-time packet handling (use carefully!) |

The Legacy Blueprint of IPv4

| Class | Range | Mask | Private Range | Hosts per Net | Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1–126 | /8 | 10.0.0.0/8 | 16M | Large Orgs |

| B | 128–191 | /16 | 172.16.0.0/12 | 65K | Medium |

| C | 192–223 | /24 | 192.168.0.0/16 | 254 | Small |

| D | 224–239 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Multicast |

| E | 240–255 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Experimental |

IPv4 classes are the DNA of the Internet’s history — the old structure that shaped how we think about addresses, subnetting, and routing even today. Even though CIDR replaced classful addressing, the class concept remains critical in:

Recognizing private/public ranges

Understanding default masks

Reading legacy configurations

Building strong subnetting intuition

Summary

What Did You Learn Today?

Let’s Find Out!

Instructions

- Select the correct answer for each technology concept.

- All questions pertain directly to the networking technologies explained.

- After answering, click “See Result” to see your score and feedback.

[Return to CCNA Study Hub] — Next Stop: [Section 2 | Subnetting: Theory ] …Currently Buffering… Available Soon!